Broken Symmetries in Hartree-Fock

It’s been a busy summer, with traveling and giving talks and writing papers.

I’m back in Seattle again (yay!), and have been thinking a lot about how we get the simplest models of electrons in molecules, the Hartree-Fock equations.

While most theorists know about restricted Hartree Fock (RHF) and unrestricted Hartree-Fock (UHF), not as many know that these can be derived from simple (okay, sometimes not-so-simple) symmetry considerations.

RHF and UHF are actually subgroups of a large class of problems called the generalized Hartree Fock equations. GHF allows mixed spin descriptions (not just simple spin up or spin down), as well as complex wave functions.

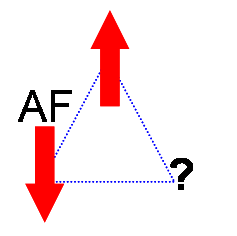

These are actually quite important for describing frustrated spin systems, like this simple triangular system

The spins can’t all align favorably, so we call it “spin frustrated”. You can try this out on your own with, say, a triangle of hydrogens or lithiums or chromiums. UHF won’t give you the lowest energy solution. It will be GHF-unstable. Only GHF can give you the lowest energy solution, since it allows the MOs to take on both “spin up” and “spin down” character.

Weird, right?

If we insist that the GHF equations are invariant with respect to spin rotations along an axis (say, the z axis), we can get the UHF equations back.

If we insist that the GHF equations are invariant to time-reversal (doesn’t that sound cool?) as well as spin rotations along all axes (x,y,z), we get the real RHF equations.

Unfortunately, the literature on it is pretty sparse, and the content pretty dense. A paradox, if I’ve ever seen one. Thankfully, I found you can derive all the relationships using the tools of linear algebra.

The results are illuminating, and it’s fun to see how the different broken symmetry HF solutions relate to each other.

So here’s my take on re-deriving the different HF classes from generalized Hartree-Fock!

We want to classify broken symmetry wave function by investigating how they transform under the action of the invariance operators \({\hat{g}}\) constituting the symmetry group \({\mathcal{G}}\) of the spin-free electronic Hamiltonian \({\hat{H}}\) which is equivalent to

\[\hat{g}\hat{H}\hat{g}^{-1} = \hat{H}, \qquad (\forall \hat{g} \in \mathcal{G}). \ \ \ \ \ (1)\]This simply means \({\hat{H}}\) is invariant to transformation by \({\hat{g}}\), whatever \({\hat{g}}\) may be. In general, when \({\vert \psi\rangle}\) is an eigenstate of \({\hat{H}}\), then \({\hat{g}\vert \psi\rangle}\) is also an eigenstate belonging to the same eigenvalue as \({\psi\rangle}\).

Now, exact eigenstates of \({\hat{H}}\) can be chosen to be simultaneous eigenstates of the various symmetries in \({\mathcal{G}}\). In contrast, for approximate variational wave functions (e.g. Hartree-Fock) the symmetry requirements represent additional constraints.

This is Löwdin’s ‘‘symmetry dilemma’’.

To state this dilemma again, we know the exact solution (lowest energy solution) will have certain symmetries, but if we include these symmetries in our approximate, variational Hamiltonian, we can only raise the energy and not lower it.

This means we can get closer to the exact solution by removing physical constraints! This is troublesome, but not a huge deal in practice.

It’s crucial to recognize that this problem arises only because we use an approximate independent-particle Hamiltonian.

There are several ways to break the single-determinental Hartree-Fock model into its various broken symmetry subgroups. However we do this, what we ultimately want to determine is the form of the operators \({\hat{A}}\) that are invariant with respect to similarity transformations by various subgroups \({\mathcal{H} \subset \mathcal{G}}\), i.e.

\[\hat{h}\hat{A}\hat{h}^{-1} = \hat{A}, \qquad (\forall \hat{h} \in \mathcal{H} \subset \mathcal{G}) \ \ \ \ \ (2)\]I find it easier to put \({\hat{A}}\) into a finite basis and treat this problem with the tools of linear algebra.

The basis for our independent particle model will be the spinor basis,

\[\vert \alpha\rangle = \left( \begin{array}{c} 1 \\ 0 \end{array} \right), \qquad \vert \beta\rangle = \left( \begin{array}{c} 0 \\ 1 \end{array} \right), \qquad \hbox{and} \quad \vert \alpha\rangle\langle\alpha\vert = \vert \beta\rangle\langle\beta\vert = \mathbf{I}_2 \ \ \ \ \ (3)\]so any arbitrary spin function can be written

\[\vert p\rangle = p_1\vert \alpha\rangle + p_2\vert \beta\rangle = \left( \begin{array}{c} p_1 \\ p_2 \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (4)\]We will only worry about one body operators \({\hat{A}}\), which include the Fock operator as well as the unitary parameterization of the single determinant (c.f. Thouless representation).

Putting \({\hat{A}}\) into a spinor basis gives us

\[\hat{A} = \vert i\sigma_1\rangle\langle i\sigma_1\vert \hat{A} \vert j \sigma_2 \rangle \langle j \sigma_2 \vert = A_{i\sigma_1,j\sigma_2} \vert i \sigma_1 \rangle \langle j \sigma_2 \vert = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{A}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (5)\]with

\[\left(A_{\sigma_1 \sigma_2}\right)_{ij} \in \mathbb{C} \quad \hbox{and} \quad \sigma_1,\sigma_2 \in \alpha,\beta \ \ \ \ \ (6)\]Or, in second quantization

\[\hat{A} = \sum\limits_{ij} \sum\limits_{\sigma_1,\sigma_2} A_{i\sigma_1,j\sigma_2} a^{\dagger}_{i\sigma_1} a_{j\sigma_2} = \sum\limits_{ij} \sum\limits_{\sigma_1,\sigma_2} A_{i\sigma_1,j\sigma_2} \hat{E}^{i \sigma_1}_{j \sigma_2} \ \ \ \ \ (7)\]The transformation properties of \({\hat{A}}\) under symmetry operations can be determined by examining the transformation of the \({U(2n)}\) generators \({\hat{E}^{i \sigma_1}_{j \sigma_2}}\), but it is much simpler to consider the transformations of the \({2\times2}\) (block) matrix \({\mathbf{A}}\), e.g.

\[\hat{h} \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{A}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right)\hat{h}^{-1} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{A}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{A}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (8)\]Basically, we are looking for the constraints on \({\mathbf{A}}\) that make the above equation true, for any given symmetry operation.

The general invariance group of the spin-free electronic Hamiltonian involves the spin rotation group SU(2) and the time reversal group \({\mathcal{T}}\), i.e. SU(2) \({\otimes \mathcal{T}}\). SU(2) can be given in terms of spin operators,

\[\hbox{SU(2)}=\{ U_R (\vec{n},\theta) = exp(i\theta \sum\limits_{a=1}^3 \hat{S}_a \hat{n}_a ); \vec{n} = (n_1, n_2, n_3); \vec{n} \in \mathbb{R}^3; \vert \vert \vec{n}\vert \vert = 1, \theta \in (-2\pi, 2\pi] \} \ \ \ \ \ (9)\]All of this amounts to performing rotations in spin space. The form looks awfully similar to rotations in 3D space (in fact, the relationship between rotations in spin space and 3D space is much deeper than that). The time reversal group is given as

\[\mathcal{T} = \{ \pm \hat1, \pm \hat{\Theta} \} \ \ \ \ \ (10)\]In general,

\[\hat{\Theta} = \hat{U}_R({\vec{e}}_2,-\pi)\hat{K} = exp(-i\pi\hat{S}_2)\hat{K} \ \ \ \ \ (11)\] \[\hat{\Theta}^{-1} = - \hat{\Theta} = exp(i\pi\hat{S}_2)\hat{K} \ \ \ \ \ (12)\]Where \({\hat{K}}\) is the complex conjugation operator.

There is nothing special about using \({\hat{S}_2}\), it’s just convention.

Time reversal doesn’t really affect time per se, but rather changes the direction of movement, be it linear momentum or angular momentum.

It’s an antiunitary operator (it must be, in fact) that consists of the spin-looking part (unitary) and then the complex conjugation operator (antiunitary), to be antiunitary overall. It affects electrons by flipping their spin and then taking the complex conjugate.

One final detail about the symmetry operators before we go on, and that is to observe that since SU(2) is a double cover, if we rotate in spin space by \({2\pi}\), we flip the sign of the wave function. If we rotate by another \({2\pi}\), we get the original state back. This is characteristic of fermions, of which electrons are a part.

Let us now consider the unitary transformations of the form \({U= exp(i\hat{B})}\) where \({\hat{B} = \hat{B}^{\dagger}}\), acting on some operator \({\hat{A}}\).This is valid for any unitary transformation that depends on a continuous parameter (which we have absorbed into \({\hat{B}}\)). We insist

\[\hat{A} = \hat{U}\hat{A}\hat{U}^{-1} = e^{(-i\hat{B})} \hat{A} e^{(i\hat{B})} \ \ \ \ \ (13)\]Now, by the Baker-Campbell-Hausdorff transformation, we can rewrite the right hand side as

\[e^{(-i\hat{B})} \hat{A} e^{(i\hat{B})} = \hat{A} + \left[\hat{A},i\hat{B}\right] + \frac{1}{2!} \left[\left[\hat{A},i\hat{B}\right],i\hat{B}\right] + \cdots \ \ \ \ \ (14)\]Since by definition \({\hat{A} = e^{(-i\hat{B})} \hat{A} e^{(i\hat{B})}}\) It suffices to show that the constraints on \({\hat{A}}\) introduced by the symmetry operation are satisfied when \({\left[\hat{A},i\hat{B}\right] = 0}\).

This is an excellent result, because it means that we can just look at how the \({2\times2}\) matrix \({\mathbf{A}}\) transforms under the Pauli spin matrices which define the SU(2) spin rotation as well as the time-reversal operation (in the time-reversal case, we can use the BCH expansion of the unitary part \({\hat{S}_y}\) and then absorb the complex conjugation into the commutator expression).

We can show how RHF, UHF, and GHF all fall out of the different symmetry combinations (or lack thereof).

From here on out, I’ll drop the hats on my operators for clarity.

Let’s start by considering how many different types of symmetry subgroups we can have. A moments thought at the form of the spin rotation and time-reversal groups gives the following subgroups:

\({\mathbf{I}}\). This means there is no symmetry.

\({\Theta}\). This means we are just symmetric to time-reversal symmetry.

\({K}\). Only symmetric to complex conjugation.

\({S_z}\). Only symmetric to spin rotations about the z-axis.

\({S_z}\),\({\Theta}\). Symmetric to both spin rotation about z, as well as time-reversal symmetry.

\({S_z}\), \({K}\). Symmetric to spin rotation about z, as well as complex conjugation.

\({S^2}\). Symmetric to all spin rotations.

\({S^2}\), \({\Theta}\). Symmetric to all spin rotations and time reversal symmetries.

That’s it! That’s all the cases you can get.

Let’s go through them, case by case, using the complex Fock matrix as an example, i.e.

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (15)\]Where we solve, for each symmetry (or group of symmetries),

\[\mathbf{h} \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right)\mathbf{h}^{-1} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (16)\]where \({\mathbf{h}}\) is the generator of the symmetry.

\({\mathbf{I}}\). No symmetry.

In this case, our transformation on \({\mathbf{F}}\) is rather simple. It looks like

\[\mathbf{I} \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right)\mathbf{I}^{-1} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (17)\]So we get no constraints. We can mix spin, as well as take on complex values. This is the structure of the complex generalized Hartree Fock (GHF) Fock matrix.

\({K}\). Complex conjugation symmetry.

If the only symmetry that holds is complex conjugation, our transformation looks like

\[K \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right)K= \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta}^{*} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (18)\]Note that \({K}\) is its own inverse. It also only acts to either the left or the right. The asterisk indicates complex conjugation (not and adjoint!).

The constraint we get here is that the values of the Fock matrix have to be identical on complex conjugation. Since this can only happen if the values are real, we get the real GHF Fock equations.

\({\Theta}\). Time reversal symmetry.

Now we start to get slightly more complicated. Using the Pauli matrix

\[\sigma_2 = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (19)\]To represent the unitary \({S_2}\) operation gives us

\[-i\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & -i \\ i & 0 \end{array} \right) K \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) i K \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & i \\ -i & 0 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta}^{*} & -\mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha}^{*} \\ -\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (20)\]We see that this really only introduces two constraints, so we choose to eliminate \({\mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha}}\) and \({\mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta}}\). This gives the final result of paired GHF, or

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ -\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (21)\]\({S_z}\). Rotation about spin z-axis.

Here we use the Pauli matrix

\[\sigma_3 = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (22)\]And show that

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & -\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ -\mathbf{F}_{\beta\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (23)\]which is only satisfied if

\[\mathbf{F} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (24)\]This gives us the complex version of UHF. We see invariance with respect to \({S_z}\) results in two separate spin blocks, with no restriction on whether they take real or complex values, or the dimension of either spin block.

\({S_z}\),\({\Theta}\). Rotation about spin z-axis and time reversal.

We are now at the point where we examine the effect of invariance to multiple symmetry operations.

It might concern you that considering multiple symmetry operations means that the order in which we perform symmetry operations matters. In general symmetry operations do not commute, but we will see that for our purposes order really doesn’t matter. Because we insist on invariance, the multiple symmetries never actually act on each other, therefore we don’t need to consider the commutator between them.

Or, put a different way, because each symmetry operation returns the system to its original state, we can consider each operation separately.The system contains no memory of the previous symmetry operation.

We can show this another way using the BCH expansion. Consider two symmetry operations on \({F}\) parameterized by \({A}\) and \({B}\):

\[e^{(-iA)}e^{(-iB)}Fe^{(iB)}e^{(iA)} = e^{(-iA)} [F + [F,iB] + \cdots ] e^{(iA)} = e^{(-iA)}Fe^{(iA)} = [F + [F,iA] + \cdots ] \ \ \ \ \ (25)\]Which is true if and only if = [F, iA] = 0 Which decouples \({A}\) and \({B}\). Considering multiple symmetry operations only gives us more constraints, and order doesn’t matter. Let’s see it in action then for time reversal and z-axial spin symmetry. Using the results for time reversal symmetry, we have

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ -\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} \end{array} \right) \left( \begin{array}{cc} 1 & 0 \\ 0 & -1 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & -\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta} \\ \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\beta}^{*} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (26)\]Which means the off diagonals must go to zero, giving our final result of paired UHF,

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (27)\]\({S_z}\),\({K}\). Rotation about spin z-axis and complex conjugation.

We do a similar thing as above for rotation about spin z-axis and complex conjugation. This one is particularly easy to show, starting from the results of complex conjugation symmetry.

Since symmetry with respect to \({K}\) forces all matrix elements to be real, we just get the real version of the results of symmetry with respect to \({S_z}\) — we get the real UHF equations!

\[\mathbf{F} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right), \qquad (\mathbf{F} \in \mathbb{R}) \ \ \ \ \ (28)\]\({S^2}\),\({S_z}\). Rotation about all spin axes.

We finally move onto invariance with respect to rotations about all spin axes. Again, this is a little weird because these operations aren’t commutative, but we have already shown that insisting on invariance leads to a decoupling of the symmetry operations.

(I should mention that if you are still unsure of this, feel free to brute force through all orders of symmetry operations. You’ll see that it makes no difference.)

Two things worth mentioning here: first, technically \({S_z}\) is already a part of the total spin rotation group, so it’s a little weird to separate them into \({S^2}\) and \({S_z}\), but we understand this as drawing the distinction that you can be symmetric to \({S_z}\) but not \({S^2}\).

If you are invariant to \({S^2}\), though, you will be invariant to \({S_z}\).

Second, while \({S^2}\) does technically have an operator representation, it is not a symmetry operation. Think about the form of the operator \({S^2}\): it’s essentially the identity, right? So when we say invariant with respect to \({S^2}\), what we really mean is that we are invariant to the whole spin rotation group, \({S_x,S_y,S_z}\).

To show invariance with respect to the spin group, it suffices just to consider any two spin rotations, since each spin operator can be generated by the commutator of the other two.

You can show this using the Jacobi identity. Say we are looking the invariance of \({F}\) with respect to generators \({A}\), \({B}\), and \({C}\), and \({[A,B] = iC}\) (like our spin matrices do). We want to show

\[[F, A] = [F, B] = 0 \implies [F, C] = 0\]The Jacobi identity tells us

\[[[A, [B, F]] + [B, [F, A]] + [F, [A, B]] = 0\]Now, by definition the first two terms are zero, and we can evaluate the commutator of \({[A,B] = iC}\), which means if \({[F,A] = [F,B] = 0}\), then it must follow that \({[F,C] = 0}\) as well (the imaginary in front doesn’t make a difference; expand to see).

That being said, we can evaluate invariance with respect to all spin axes by using the results of \({S_z}\) and applying the generator \({S_x}\) defined by Pauli matrix \({\sigma_2}\) to it, where

\[\sigma_2 = \left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (29)\]Applying this gives

\[\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right)\left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} \end{array} \right)\left( \begin{array}{cc} 0 & 1 \\ 1 & 0 \end{array} \right) = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (30)\]Which means that \({\mathbf{F}_{\alpha\alpha} = \mathbf{F}_{\beta\beta}}\), or

\[\mathbf{F} = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{R} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{R} \end{array} \right), \qquad (\mathbf{F}_{R} \in \mathbb{C}) \ \ \ \ \ (31)\]Invariance in this symmetry group results in the complex RHF equations, where the alpha and beta spin blocks are equivalent. Thus orbitals are doubly occupied.

\({S^2}\),\({S_z}\),\({\Theta}\),\({K}\). All spin rotations and time reversal.

Given the results we just obtained above, and understanding that time reversal contains the \({S_y}\) operator, we only need to take the previous results and make them invariant to complex conjugation. This is very simple, and we see that

\[K\left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{R} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{R} \end{array} \right)K = \left( \begin{array}{cc} \mathbf{F}_{R}^{*} & \mathbf{0} \\ \mathbf{0} & \mathbf{F}_{R}^{*} \end{array} \right) \ \ \ \ \ (32)\]In other words, the real RHF equations, since invariance with respect to complex conjugation forces the elements to be real.

N.B. Most of this work was first done by Fukutome, though my notes are based off of Stuber and Paldus. The notes here agree with both authors, though the derivations here make a rather large departure from the literature. Thus, it is helpful to reference the following work:

Fukutome, Hideo. ‘‘Unrestricted Hartree-Fock theory and its applications to molecules and chemical reactions.” International Journal of Quantum Chemistry 20.5 (1981): 955-1065.

Stuber, J. L., and J. Paldus. ‘‘Symmetry breaking in the independent particle model.” Fundamental World of Quantum Chemistry, A Tribute Volume to the Memory of Per-Olov Löwdin 1 (2003): 67-139.

I’d strongly recommend looking at Stuber and Paldus’ work first. Their terminology is more consistent with mainstream electronic structure theory.